New Agers are counting down the days until the

Mayan calendar ends in 2012. Evangelical Christians long for the Rapture.

Extropians dream of the Singularity, when computers will surpass human

intelligence and technology will transcend all limits. Doomers stockpile

freeze-dried food as they wait for civilization to crash and burn around them. What do they all have in common?

They’re all wrong.

For almost 3,000 years apocalypse prophecies have

convinced people all over the world that the future is about to give them the

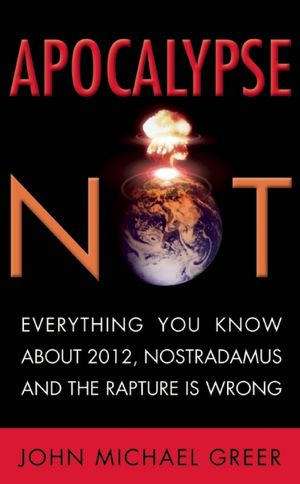

world they want instead of the world they’ve got. John Michael Greer’s Apocalypse

Not is a lively and engaging survey of predictions about the end of the

world, along with the failed dreams and nightmares that have clustered around

them.

Have a look:

A strong case could be made for the idea that

storytelling is one of humanity’s oldest and most powerful technologies. As

soon as the extraordinary gift of human language finished emerging out of

whatever forgotten precursors gave it birth, hunters back from the chase and

gatherers returning with nuts and tubers doubtless started describing their day’s

experiences in colorful terms, and their listeners picked up more than a few

useful tips about how to track an antelope or wield a digging stick: the glory

of the impala’s leap and the comfortable fellowship of gatherers working a

meadow together wove themselves into the stories and the minds of the audience,

and helped shape their experience of the world. Stories still do that today, whether

they’re woven into the daily news, dressed up as religious or secular ideology,

or in their natural form as stories one person tells another.

Some of these stories are very, very old. Most of

the stories that people nowadays call “mythology,” in particular, have roots

that run back far into the untraceable years before anybody worked out the

trick of turning spoken words into something more lasting. Read through the

myths of every culture and you’ll find certain themes repeated endlessly: stories

of a golden age or paradise back in the distant past when things were much

better than they are now; stories of a worldwide flood from which a few

survivors managed to escape to repopulate the world; stories of terrible

monsters and the heroes or heroines who killed them; stories of heroes or

heroines of a different kind, who died so that other people might have a more

abundant life—all these and others are part of the stock in trade of myth

around the world, shared by peoples whose ancestors, at least until modern

times, had no contact since the end of the last Ice Age.

Some modern theorists, starting from this evidence,

have argued that these core themes and the stories based on them are somehow

hardwired into the human brain. This may or may not be true—the jury’s still

out on the question— but it’s definitely the case that most of the themes of mythology

appear on every continent and in every age. If they were invented, the event

happened so long ago that no trace remains of the inventor or the time and

circumstances of the invention.

The apocalypse meme is one of the few exceptions. Hard

work by a handful of perceptive scholars, most notably historian of religions

Norman Cohn, has traced it back to a specific place, time, and person. The

place was the rugged region of south central Asia that today is called Iran,

the time was somewhere between 1500 and 1200 BCE, and the person was

Zarathustra, the prophet of the religion now called Zoroastrianism.

No comments:

Post a Comment